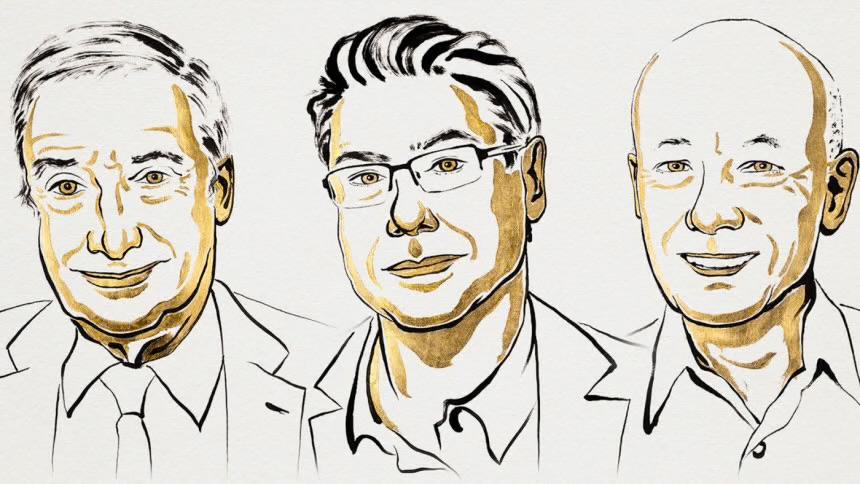

2025 Nobel Prize in Economics Goes to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt

illustration: Niklas Elmehed, Copyright: Nobel Prize Outreach

For most of human history, the story of our economic lives was one of near-total stagnation. For thousands of years, from the era of hunter-gatherers to the rise of vast agrarian empires, the standard of living for the average person barely changed. Progress was glacial, and life was, for most, a struggle for subsistence. Then, around the year 1750, something extraordinary happened. A switch was flipped, and the world ignited. This was the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, the moment that bent the curve of human history into the shape of a hockey sticka long, flat handle of stagnation followed by a sudden, explosive, and sustained upward blade of growth. But what was the secret ingredient that unlocked this sustained prosperity?

This year, the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences has been awarded to the three brilliant minds whose work provides the most compelling explanation for this dramatic shift: Joel Mokyr of Northwestern University, and the collaborative duo of Philippe Aghion from the Collège de France and Peter Howitt from Brown University. Their research, while different in method, converges on a powerful narrative about how humanity escaped the trap of scarcity and unleashed the forces of innovation that built the modern world. They have given us the definitive story of the spark that lit the fire and the engine that keeps it burning.

Why the Revolution Began?

The fundamental question has always been: why then, and why in Europe? What was the secret ingredient that previous civilizations lacked? Economic historian Joel Mokyr, now 79, dedicated his career to answering this very question. He argued that the "Intellectual Origins of Modern Economic Growth" lay not just in new machines, but in a revolutionary change in the nature of knowledge itself.

Mokyr’s profound insight was that true, sustained progress requires the fusion of two distinct types of knowledge. The first is what he calls prescriptive knowledge. This is the practical, hands-on knowledge of "how" to do something. It is the world of recipes, techniques, instructions, and craftsmanship. A blacksmith knew how to forge steel, and a weaver knew how to operate a loom. This type of knowledge had existed for millennia, passed down through apprenticeships, but it often lacked a deeper understanding of the principles at play.

The second, and more crucial, category is propositional knowledge. This is the theoretical understanding of why things work. It encompasses the scientific principles, the natural laws, and the fundamental mechanics of the world. It’s knowing not just that a certain mixture creates a stronger metal, but understanding the chemical reactions that make it so.

For most of history, these two streams of knowledge ran in parallel, rarely touching. Artisans tinkered and improved things through trial and error, while philosophers and scientists debated abstract principles with little practical application. The Industrial Revolution, Mokyr argues, was the moment those two streams merged into a powerful, self-reinforcing river. The scientific discoveries of the Enlightenment began feeding directly into practical invention. The steam engine wasn't just a clever gadget; it was the product of a growing understanding of atmospheric pressure and vacuums. In turn, the challenges of building better engines and machines created new questions and problems that drove further scientific inquiry. This feedback loop between "how" and "why" was the spark.

However, Mokyr emphasizes that this intellectual breakthrough needed fertile ground to grow. It also required a society with skilled artisans and engineers capable of translating theoretical ideas into commercially viable products. Furthermore, it demanded a cultural and political environment open to change. Europe, politically fragmented and competitive, provided this unique setting. Unlike monolithic empires that could stifle disruptive ideas, Europe's competing states ensured that if one ruler suppressed progress, innovators could simply take their ideas elsewhere. This competition and openness allowed the fragile flame of progress to survive and spread.

The Engine of Growth

If Mokyr explained the ignition, then Philippe Aghion, 69, and Peter Howitt, 79, built the definitive blueprint for the engine that has powered growth ever since. Using the language of mathematics, they formalized a concept first coined by economist Joseph Schumpeter: creative destruction.

Their most famous paper, "A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction" provides a beautifully elegant framework for understanding the messy, chaotic, and yet ultimately productive nature of market competition. They show that economic growth is not a smooth, predictable process but a relentless cycle of innovation and displacement.

They ask us to imagine the economy as a series of quality ladders. Companies invest heavily in research and development (R&D) in a race to create a better product or a more efficient production method-to take a step up the ladder. If a company succeeds, its reward is immense: a patent, temporary monopoly profits, and market dominance. This success, however, paints a target on its back. The huge profits of the leader create a powerful incentive for rivals to invest even more in R&D, striving to invent something even better and leapfrog to the top.

When a successful innovator launches their superior product, they effectively "topple" the old market leader. The previous champion’s profits vanish, its technology becomes obsolete, and its market share is stolen. Yesterday’s news is replaced by today’s breakthrough. This is the destructive part of the cycle. But the creative side is what drives society forward. Consumers get higher-quality products, new industries are born, and overall productivity rises.

Aghion and Howitt’s model brilliantly shows how this turbulent process at the micro-level of individual firms and markets adds up to a relatively smooth and steady growth path for the economy as a whole. While one market might jump dramatically with a new breakthrough, these individual shocks average out across thousands of markets. They distilled this complex dynamic into a simple, powerful equation:

Economic Growth = (The size of each innovation step) × (How often the steps arrive)

This framework reveals that growth is not an accident. It is a direct result of a competitive process that channels ambition and ingenuity into a constant search for improvement.

A Lesson for Our Time

The combined work of these three laureates offers a unified and profound story. Mokyr provides the historical narrative of how the necessary intellectual and cultural conditions for the Industrial Revolution first came together. Aghion and Howitt provide the mathematical model of the competitive engine that took over, making innovation a continuous and self-sustaining process.

As the Nobel Committee highlighted, their work is a powerful reminder that progress cannot be taken for granted. The engine of creative destruction requires constant fuel and maintenance. As John Hassler, chair of the prize committee, warned,

“We must uphold the mechanisms that underlie creative destruction, so that we do not fall back into stagnation.”

Today, this warning is more relevant than ever. Aghion has cautioned that rising protectionist trade policies and the immense power of monopolistic tech firms could stifle the very competition that fuels innovation. When a few dominant players can buy out or crush any potential rival, the incentive for outsiders to climb the ladder diminishes. Without a constant threat from new innovators, today's giants have less pressure to improve, and the engine of growth can sputter.

The legacy of Mokyr, Aghion, and Howitt is a deep and empowering understanding of our own prosperity. They have shown that our modern world was not built by central plans or government decree, but by the dynamic interplay of ideas, competition, and the relentless cycle of creation and destruction. Their work is a call to action: to protect the openness, champion the competition and foster the spirit of inquiry that first launched the hockey stick of human progress and continues to propel it forward.